How >100,000 CFU became synonymous with UTI

For decades, undiagnosed pyelonephritis caused chronic kidney disease and death. Quantitative urine culture emerged as a tool to prevent these bad outcomes. But did we get the cutoff right?

Readers of Origin Stories know that I love writing about numerical thresholds (e.g., >250 PMNs for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis or <7 g/dL to prompt a red blood cell transfusion). I also recently wrote about a surrogate end-point (asymptomatic DVT), arguing that it may not provide an appropriate basis for using venous thromboembolism chemoprophylaxis.

The use of 100,000 colony-forming units (CFU) to diagnose a urinary tract infection (UTI) presents another fascinating case study, this time involving both a numerical threshold and a surrogate endpoint. The last few years have seen this numerical cut-off revisited and questioned. To see why, let’s go back to its origin.

Historical Arc

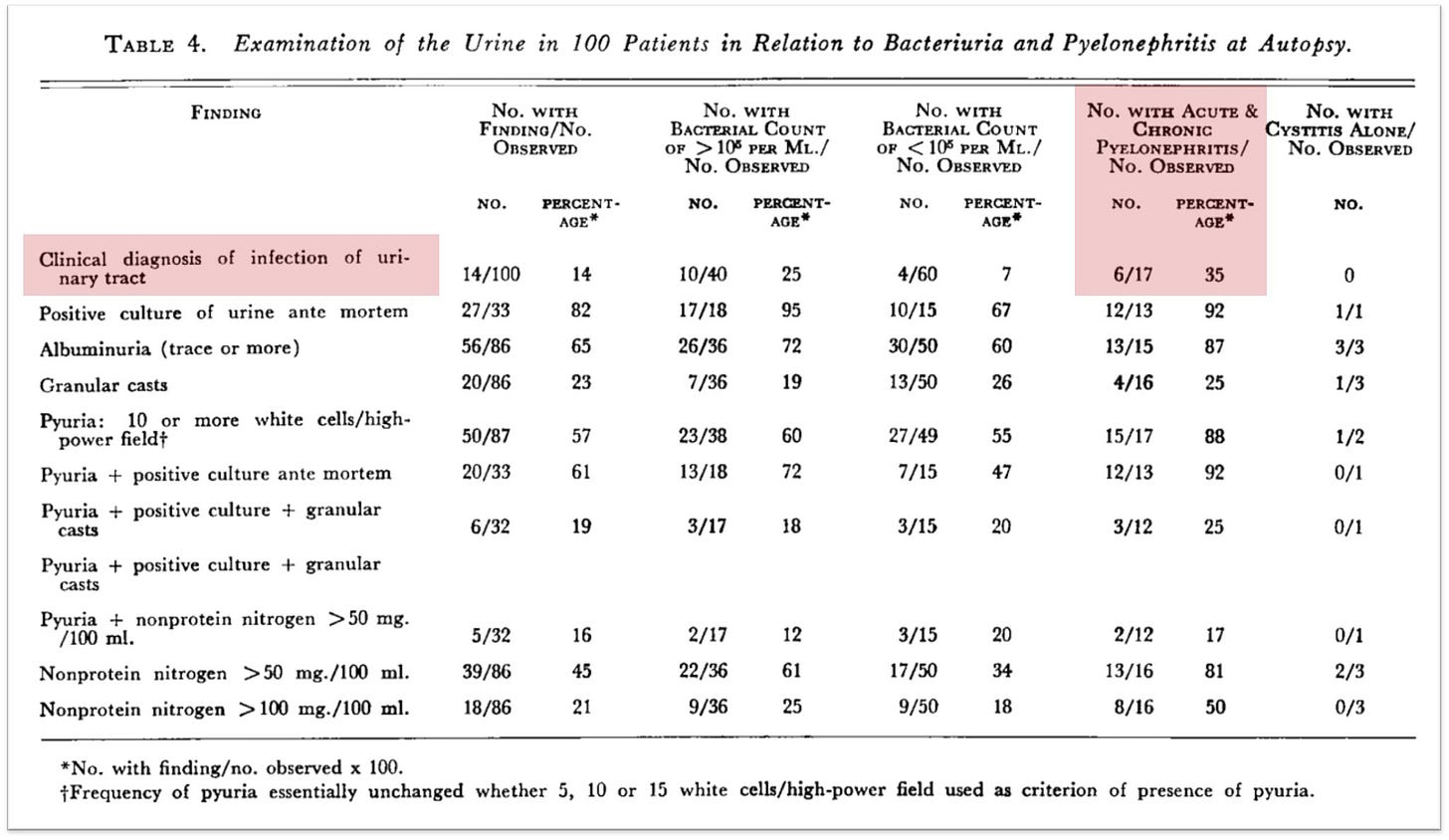

Much of the reliance on quantitative urine cultures grew out of the observation that many patients were found to have pyelonephritis on autopsy, never having been diagnosed antemortem. In one cohort published in The New England Journal of Medicine in 1957, just 35% of patients with autopsy evidence of pyelonephritis had a clinical diagnosis before death.1

Although pyelonephritis in 2025 is undoubtedly an important condition warranting diagnosis and treatment, in the 1950s it was considered far more dreadful, contributing to death in nearly 33% of cases discovered at autopsy. And it was felt a significant cause of morbidity; as one review put it, “Chronic pyelonephritis appears to be etiologically related to malignant hypertension and there are strong, but not un-challenged, indications of an etiologic relationship to benign hypertension.”

Reliance on symptoms alone was inadequate.2 Clinicians needed another, more reliable and straightforward marker of infection.

Enter the quantitative urine culture!

The idea that we might use urine culture to diagnose urinary tract infection may seem obvious, but this has not always been the case. As noted by Platt in 1983, “Although symptomatic urinary tract infection has been a well-recognized entity for many decades, the use of quantitative bacteriology to identify infections first received serious attention in 1941 when Marple reported that approximately one-fifth of hospitalized women had large numbers of Gram-negative bacilli in the urine.”

There are at least three ways to collect a urine specimen for culture and bacterial quantification: (1) suprapubic aspiration; (2) catheterization; (3) midstream free void.

Of course, there is a problem with any of these methods: false-positive urine cultures (i.e., “contamination”), particularly with the voided urine samples. It is not enough to have bacteriuria. We need a value above which contamination becomes less likely and infection becomes more likely. The question became, how many bacteria are enough?

In the 1950s, Edward Kass and others performed a series of studies to determine the number of bacteria in the urine that supported a diagnosis of UTI. When suprapubic aspiration is used, most studies have consistently shown:

A bimodal distribution with most patients with either zero bacteria or >10⁵ CFU/ml.

Approximately 25% of patients had values <10⁵ CFU/ml, suggesting that the value is too insensitive.

What about sterile catheterization? In a 1956 report published in Transactions of the Association of American Physicians, Kass presented data correlating the number of bacteria per milliliter of urine (obtained via catheterization) with a diagnosis of pyelonephritis.

As far as I can tell, Kass used clinical features as the “gold standard” for diagnosing pyelonephritis. A bit circular, particularly given the concerns about asymptomatic disease. Still, that’s what was done. As shown in the figure below, 95% of individuals with pyelonephritis or suspected pyelonephritis had greater than 10⁵ (i.e., 100,000) CFU per mL of urine.

Notice that some patients with pyelonephritis have counts as low as 10² CFU/mL. Again, using >10⁵ CFU/ml is too insensitive, even for the more severe form of UTI.

But the opposite is also true. Studies utilizing sterile catheterization have shown that even in asymptomatic women, upwards of 50% of urine specimens will show >10⁵ CFU/ml, meaning that this cut-off can lead to overdiagnosis.

These early studies relied on suprapubic aspiration or sterile catheterization, the two methods of sample acquisition considered to be less prone to false-positive contamination. But these methods are invasive, uncomfortable, inconvenient, and not entirely benign. There was therefore an interest in whether midstream voided samples might offer a simpler alternative.

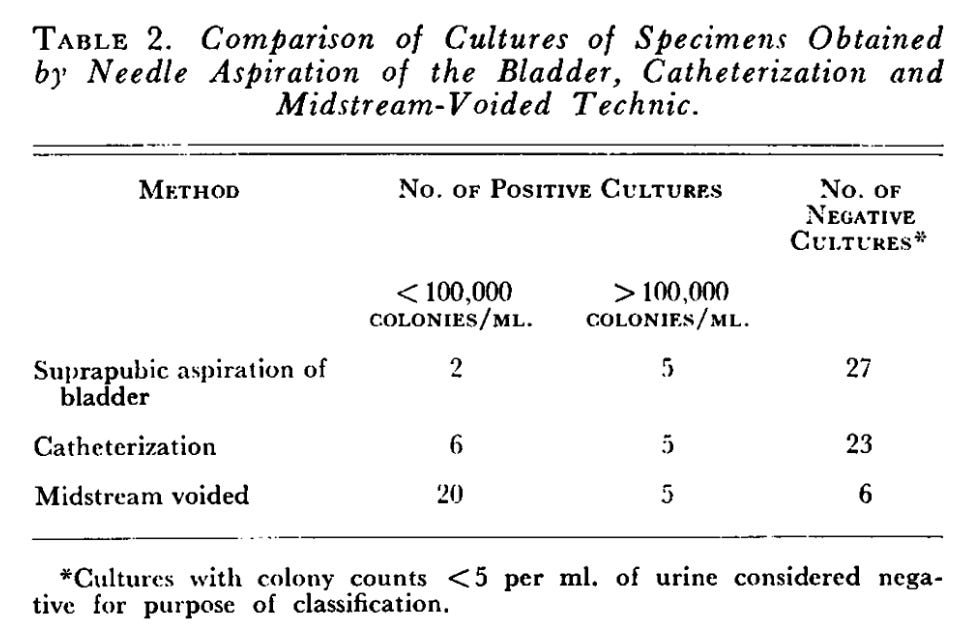

In 1958, Monzon et al. published a study in The New England Journal of Medicine in which they collected suprapubic, catheter, and midstream void samples. They included patients with possible UTI based on prior urine culture and/or a urinalysis showing proteinuria, pyuria, or bacteriuria. Table 2 provides a nice summary of the key results.

If one were to accept that suprapubic aspiration of the bladder provides a reasonable “gold standard” for the assessment of true-positive bladder bacteria, these results do not support the premise that a midstream void is an acceptable alternative.

Nonetheless, the work by Kass and others led to the practice of defining true bacteriuria for both pyelonephritis and cystitis as greater than 10⁵ CFU/mL, obtained from a midstream voided sample. There are at least three problems with this:

Combining pyelonephritis and cystitis, though convenient, may be inappropriate.

Midstream voided samples are likely to overestimate true bladder bacteriuria.3

For some, a cut-off of greater than 10⁵ CFU/mL will miss a diagnosis of pyelonephritis and/or bladder bacteriuria.

Over the next few decades, additional evidence emerged that using more than 10⁵ CFU/mL is too insensitive.

A Challenge Emerges

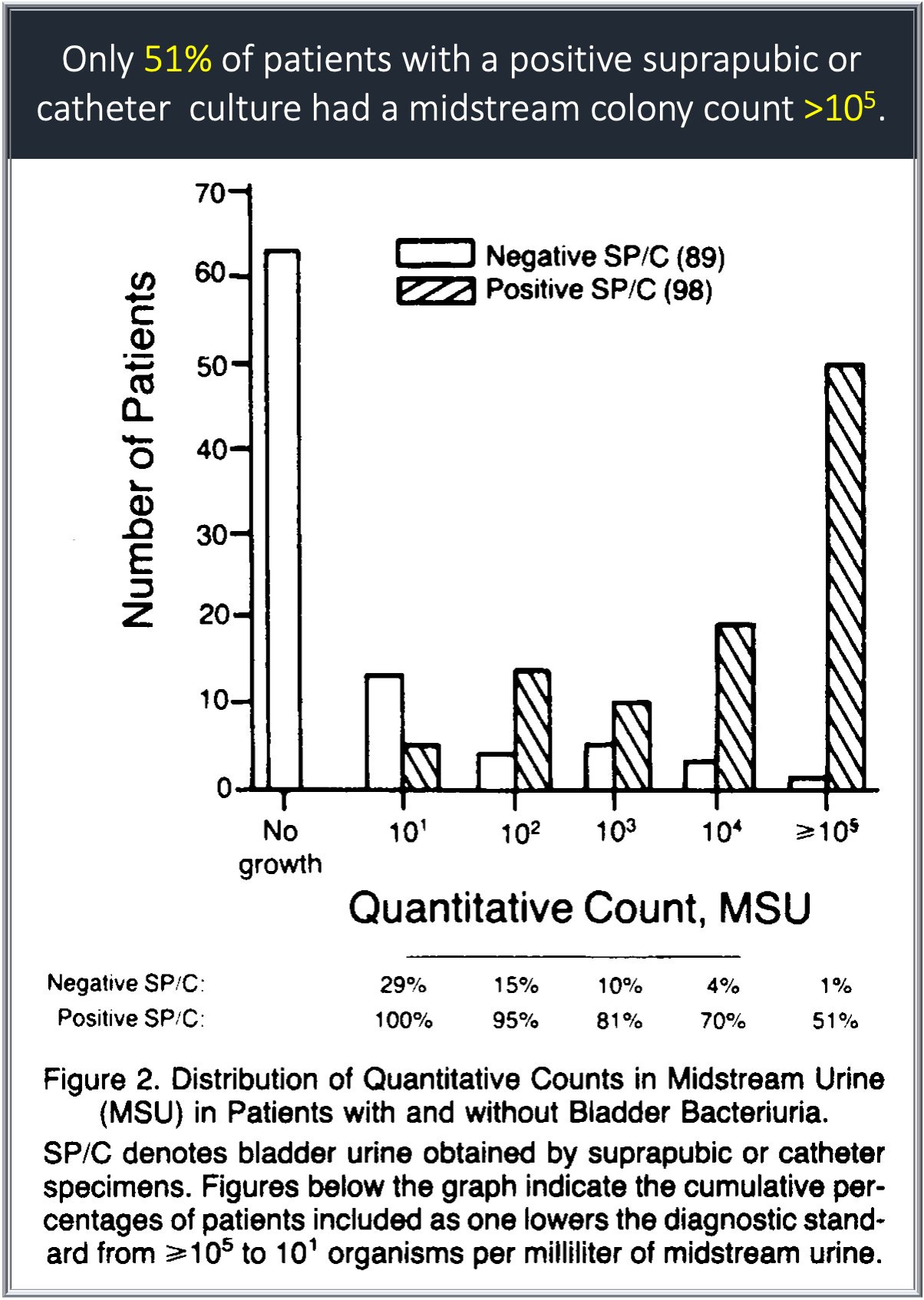

Despite the fact that Kass and others used catheter samples to quantify bacteruria, the use of voided urine samples increased. With this in mind, in 1982, Stamm et al. published a study in The New England Journal of Medicine comparing urine obtained via suprapubic aspiration or catheterization with a voided sample.4 The two former methods were used to represent a gold standard for true bladder bacteriuria. They found that >10⁵ CFU/mL has a sensitivity of only 51%. When the value was lowered to 10², the sensitivity increased to 95%.

Despite these results, in the intervening decades, >10⁵ CFU/mL continued to be used by many as the cutoff for UTI. I certainly did.

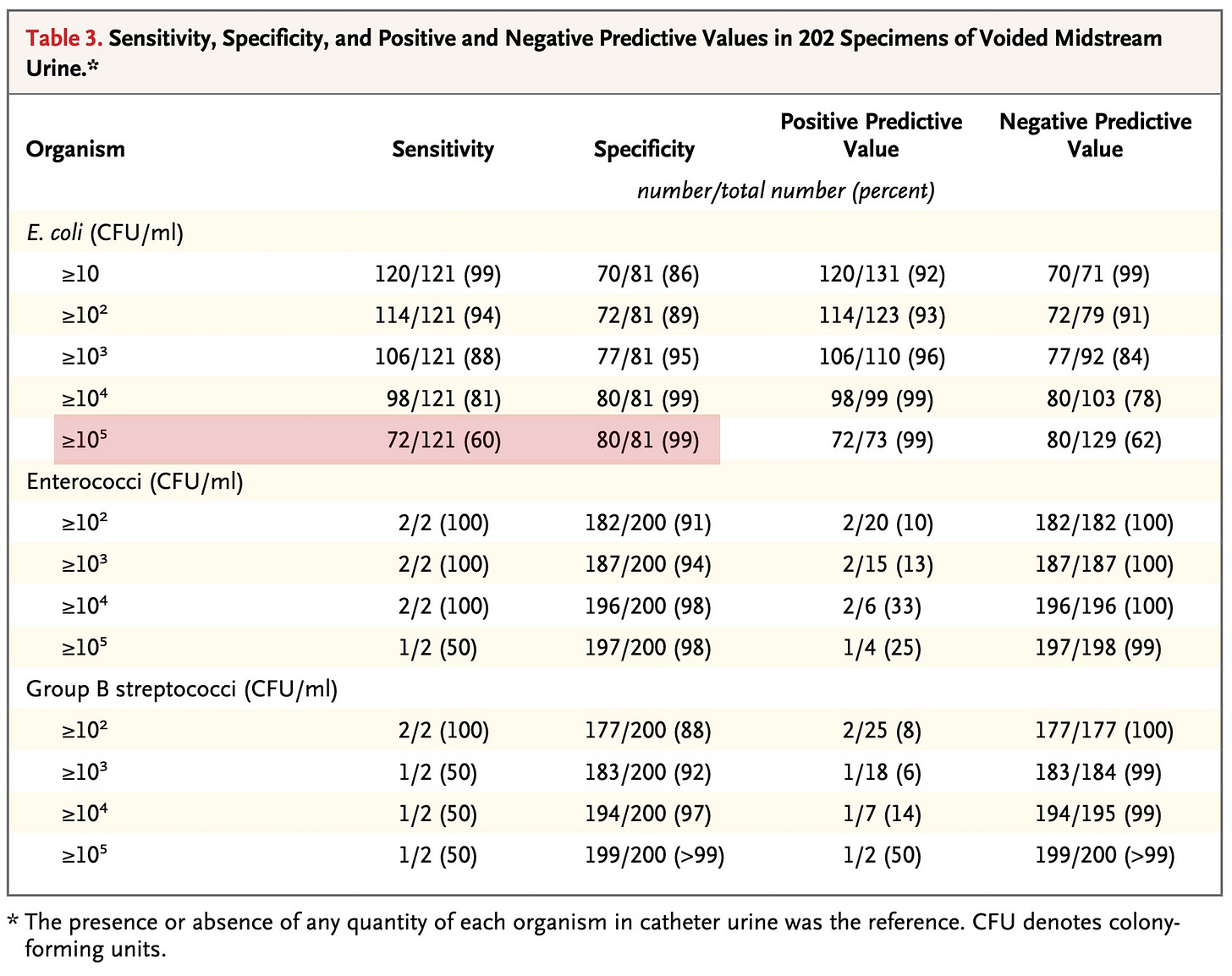

More than three decades passed. In 2013, Hooton et al. revisited the question. They examined 236 episodes of cystitis and compared urine samples obtained via catheterization with those collected via midstream voiding.5

As with prior studies, a cut-off of >10⁵ CFU/mL missed many infections (sensitivity 60% when E. coli was the pathogen). This may lead to undertreatment of patients with symptoms. And as with Stamm, when the value was lowered to 10², the sensitivity increased, this time to 94%.

The original studies by Kass and subsequent follow-up studies by Stamm and Hooton all agree: using a concentration greater than 10⁵ CFU/mL leads to missed cases of true bacteriuria in symptomatic patients.

What do guidelines suggest?

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) has not published a new guideline on the diagnosis of UTI in the last few decades.6 But other sources support the notion that a lower limit should be used.

A 2011 review published in The New England Journal of Medicine wrote that, “studies comparing voided urine specimens and bladder aspirate specimens in women with cystitis have shown that the traditional criterion for a positive culture of voided urine (10⁵ colony-forming units per milliliter) is insensitive for bladder infection.” And UpToDate writes that, “In asymptomatic patients, the standard threshold for bacterial growth on a midstream voided urine culture that reflects bladder bacteriuria as opposed to contamination is ≥105 colony forming units (CFU)/mL. However, in symptomatic individuals without an indwelling urethral catheter, lower midstream urine counts (ie, ≥102 CFU/mL) have been associated with the presence of bladder bacteriuria and thus may be indicative of a UTI.”

Despite this, I still find that most of my peers ascribe special significance to values greater than 100,000 CFU/mL. When my pretest probability of UTI is high, I have increasingly prescribed treatment for values that, years ago, I would have ignored.

Other researchers noted that autopsy evidence of pyelonephritis correlated with antemortem symptoms in just 20% of patients.

Readers may notice the differences in this approach when compared with contemporary methods for asymptomatic bacteriuria. In 2025, this condition is considered not to represent an infection, and, except for pregnancy and recent instrumentation, it is not recommended that one receive treatment.

This, of course, is why there has been an enormous push away from treating asymptomatic bacteriuria.

Important note: this study only assessed coliform bacteria (e.g., E. coli, the most common cause of UTI).

Although the use of suprapubic samples may offer a more appropriate gold standard, its use has fallen so out of favor that I understand the use of catheterization.

A more general IDSA Guide to Utilization of the Microbiology Laboratory for Diagnosis of Infectious Diseases offers that “culture of urine continues to be routinely performed using quantitative methods, with the standardized threshold in symptomatic patients of >100,000 CFU/mL for organisms identified as common pathogens; however, many sites now use either 10,000 CFU/mL or 1000 CFU/mL thresh-old based on the method of collection or patient populationas a baseline for culture workup and clinical significance.”