I’m endlessly fascinated by thresholds in medicine. Some thresholds are diagnostic. The criteria for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, for example, include a polymorphonuclear leukocyte count ≥250 cells/mm3. And someone found to have a hemoglobin A1c of ≥6.5% will carry a diagnosis of diabetes. An A1c of 6.4% just doesn’t make the cut.

Other thresholds are therapeutic. If I say “four and two” to any internal medicine intern, they immediately know I am referring to potassium and magnesium and the values below which they are expected to replete. The origin story of our incessant need to replete serum potassium to ≥4.0 is instructive and something we covered on The Curious Clinicians.

The hemoglobin1 value below which one considers a blood transfusion warrants particular attention. It provides a glimpse into how some thresholds have evolved and, I believe, will continue to evolve. As of today, November 29 2023, most patients I care for will receive a transfusion of packed red blood cells (pRBCs) if their hemoglobin falls below 7 g/dL. This hasn’t always been the case. Before tackling how we got here, a review of history will provide necessary context.

Brief history of transfusions

James Blundell, an English obstetrician, is typically credited as the first person to successfully utilize human-to-human blood transfusion. On December 22, 1818, Bundell and Henry Crane used a syringe to transfer 14 ounces (~400 mL) of blood from several donors into a patient with stomach cancer. Though unsuccessful (the patient died days later), Blundell continued to experiment with both indirect transfusions using a syringe and direct transfusions in which the donor and recipient were connected and blood was transferred without an intermediary. Despite these advancements, blood transfusions remained rare events during the remainder of the 19th century. There were just too many barriers preventing wide use.

The first major barrier was transfusion reactions, particularly disastrous hemolysis from mismatched blood. Then, in the early 20th century, Karl Landstein discovered blood groups, paving the way for cross-match testings prior to transfusion. With this innovation in place, the risk of the most feared transfusion reaction was mitigated, if not completely prevented. Transfusions soon increased in frequency though many remained direct via artery-to-vein anastomosis between donor and recipient. The persistence of this inefficient method was due to the higher likelihood of the next barrier to widespread use: clot formation outside the body.

Clotting was overcome with the introduction of sodium citrate. Its use made direct transfusion nearly obsolete and led to the emergence of blood banks in the 1930s. Now clinicians had the ability to remove and store blood for later use. And it was exactly this - whole blood transfusion - that remained the norm for an additional four decades. This is despite the fact that the final barrier - separation of blood into its parts (i.e., red blood cells, white blood cells, platelets, and plasma) - had emerged around the same time as sodium citrate. Instead, whole blood transfusion remained the standard of care well into the 1970s, when we finally saw a shift toward the use of fractionated products.

By the middle of the 1980s, the use of whole blood had essentially vanished.

With the final barrier having been lifted, the stage was set for the emergence of numerical thresholds.

The emergence of 10 g/dL as the first threshold

Given the technical constraints, poor safety profile, storage limitations, and inability to use targeted components, transfusions have historically been reserved for acute conditions. Blundell, for example, suggested transfusion only for hemorrhage endangering life. Once medicine had solved these problems, things began to change in the middle of the 20th century. Patients no longer required hemorrhage or shock. Transfusions’ newfound safety and availability expanded their use to patients whose only indication was a number. And, as demonstrated by the earliest adopters of numerical thresholds would show, an upcoming surgery.

A number of authors have cited a 1942 paper as the origin of value-based transfusion thresholds. In it, two anesthesiologists, RC Adams and John Lundy, suggest that “when concentration of hemoglobin is less than 8 to 10 grams per 100 cubic centimeters of whole blood, it is wise to give a blood transfusion before operations.” In retrospect, it is of little surprise that a numeric trigger emerged within anesthesia. This field aims to mitigate the risks of operative therapy, and the improvement in oxygen-carrying capacity that comes with increasing a patient’s preoperative hemoglobin is consistent with this goal. They, therefore, would see asymptomatic anemia as something worth remedying.2 In the years that followed, anesthesiology embraced this new strategy and began to strongly favor higher hemoglobin values before proceeding to the operating room.

Entering the 1970s, a solid shift had occurred away from exclusive condition and symptoms-based transfusion and towards a standard that included numerical thresholds. A 1972 survey of anesthesiologists found that 44% required a preoperative hemoglobin >10 g/dL before proceeding with elective surgery. Just 1.8% would move ahead with a hemoglobin between 7 and 8 g/dL. A decade and a half later, another survey study of anesthesiologists found that 65% required a preoperative hemoglobin of at least 10 g/dL.

Though there was undoubtedly practice variation, 10 g/dL had cemented its place as the standard threshold. It did so not because clinical trials showed its superiority over other thresholds.3 Instead, 10 g/dL emerged because it is a nice round number. As Welch, Meehnan, and Goodnaugh wrote in a splendid 1992 review, the use of 10 g/dL “undoubtedly reflects our preference for easily remembered digits.” Later, they write, “The age-old transfusion trigger of a hemoglobin level of [10 g/dL] is no longer defensible.”

Although 10 g/dL became the standard threshold between the 1940s and 1980s, there was always an undercurrent of resistance and caution later echoed by Welch, Meehnan, and Goodnaugh. As soon as these thresholds emerged, authors lamented their use. Writing in 1960, C.W. Graham-Stewart noted that, “whereas twenty years ago blood-transfusion was a therapeutic event, it has now become commonplace; and at times it is administered or withheld with little consideration of the real need.”

Hospitals began to implement internal guidance with the aim of combating the new normal. In 1962, Kenneth McCoy reported on the Providence Hospital blood conservation program. Recognizing that “the problem of obtaining an adequate supply of whole blood is directly related to the indications for transfusion that are adopted,” the hospital had implemented internal guidelines in 1953. Accepting that one might desire transfusion to support oxygen delivery, they suggested that an “anemic patient, otherwise well, must have seven or less grams of hemoglobin per 100 ml. of blood.”

Describing the internal guidance at St. Joseph Mercy Hospital in Ann Arbor, Michigan, Dietrich wrote in 1975 that “a hemoglobin of [7 g/dL was] arbitrarily set as positive criteria for patients presenting with anemia secondary to malignancies, iron deficiency and simple anemia. However, regardless of the hemogram, transfusion in chronic anemia was not considered justifiable unless the patient was symptomatic.” However, these internal guidelines did little to change the wider practice of injudicious transfusion. Only randomized control trials would shake medicine from its new habit. And even this gold standard couldn’t wrestle it away completely.

TRICC, TRISS, Villanueva, and many more

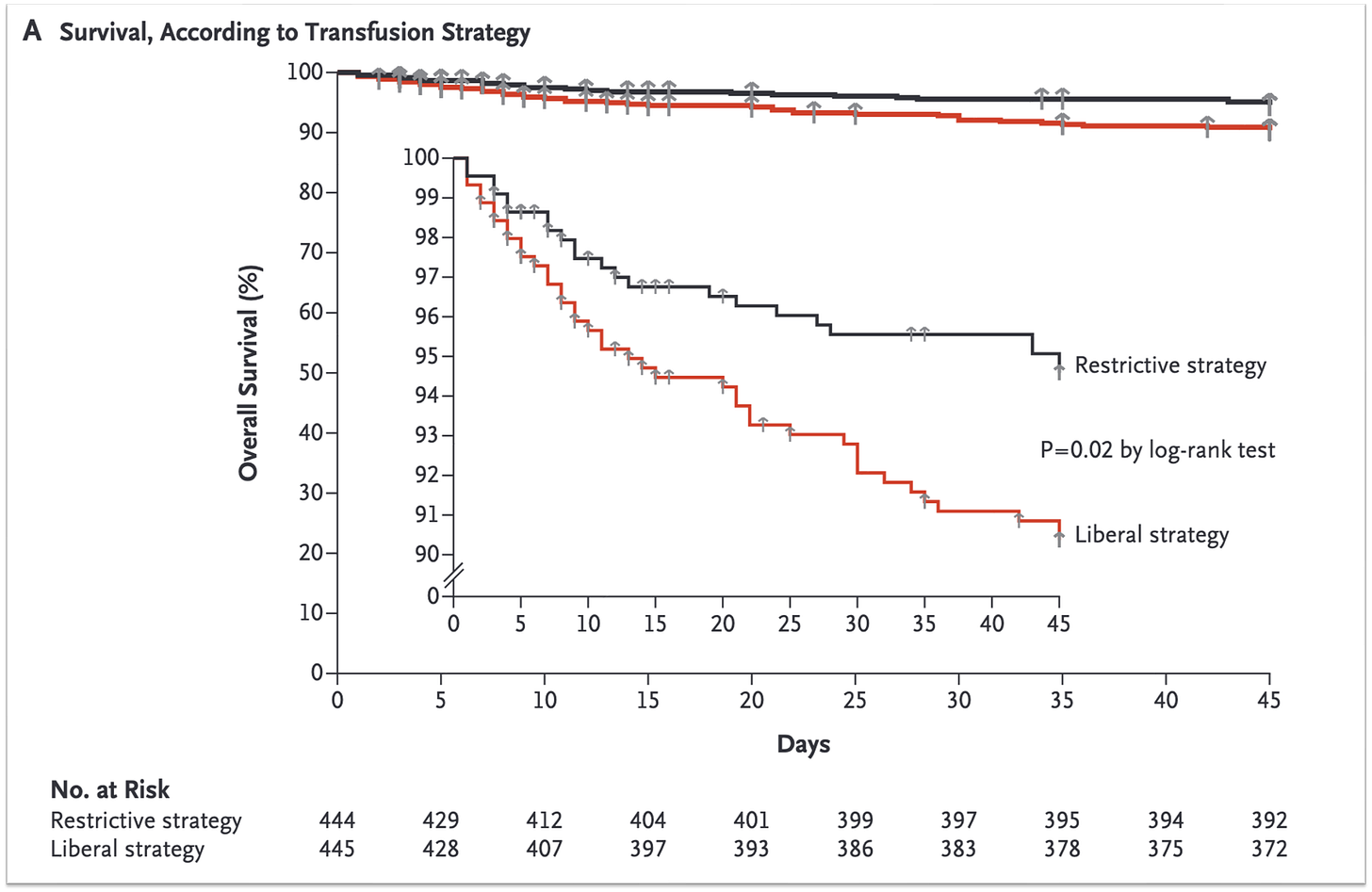

The turn of the century saw the rise of randomized control trials comparing “restrictive” and “liberal” transfusion thresholds. This era began with the TRICC trial, published in February 1999 in The New England Journal of Medicine. TRICC enrolled 838 patients with critical illness and randomized them to either a 7-9 d/gL (restrictive) or 10-12 g/dL (liberal) transfusion threshold. The results favored the 7-9 g/dL target.

As a hospitalist, the trial that most changed my practice was published in 2013 by lead author Càndid Villaneuva. This study randomized patients with acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding to receive red blood cell transfusion for a hemoglobin <7 g/dL (restrictive) or <9 g/dL (liberal). Once again, the restrictive strategy led to better outcomes.

In total >30 randomized clinical trials have been published comparing restrictive and liberal transfusion practices. The results are clear: there is no difference in 30-day mortality, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, stroke, rebleeding, thromboembolism, or infection when you wait to give blood. These studies include surgical patients and those with critical illness, acute bleeding, cancer, myocardial infarction, and others. The collective data strongly support fewer transfusions, though the exact threshold does differ based on the condition studied. Here is what UpToDate recommends:

I must offer two very important observations and caveats. First, there are no trials including patients with asymptomatic anemia. And yet, this is one of the most common indications for transfusions in my setting (acute care medicine). I repeatedly see patients with chronic anemia whose hemoglobin hovers around 7 g/dL. Then, one day, they dip below this value. When this happens, many providers immediately respond with an order for s single unit of pRBCs. Notice that a patient with a hemoglobin of 6.9 g/dL today is essentially in the same physiologic state as when the lab reported a hemoglobin of 7.0 g/dL yesterday. And it is quite likely that if we simply rechecked the value tomorrow, without transfusing, it would suddenly rise above the 7 g/dL threshold once again. This, of course, is the crux of threshold-based treatments. We know they are blunt surrogates of the true physiological measures we care about. And yet we must use them given that our inability to easily access those measures is obscured.

I also see our use of blood transfusions for an asymptomatic hemoglobin of 6.9 g/dL as an example of indication creep. Given the lack of direct evidence for what to do in this situation, we are left using whatever data is available. And what we have suggests it is safe to not transfuse until the hemoglobin hits 7 g/dL4. Implicit in this statement is that we ought to transfuse once it has fallen below 7 g/dL. However, there is no clear data supporting this practice in patients with asymptomatic anemia. Furthermore, there is no reason to assume that such a patient has the same oxygen delivery demands as those with shock, myocardial infarction, or who is undergoing major surgery. But we feel compelled to act, and 7 g/dL is the lowest number we have been offered.

This brings me to the second important caveat: we have no strong data supporting 7 g/dL over a lower value. Instead, 7 g/dL is merely the lowest number evaluated in randomized trials. And, unfortunately, I see no ongoing attempts aimed at providing guidance on either caveat. Nothing to examine whether we are justified in transfusing an asymptomatic patient with a hemoglobin of 6.9 g/dL and nothing comparing 7 g/dL to lower values in any of the populations already studied.

This means were are left with observational studies. And there is good reason to believe we can go lower than 7 g/dL. Natural experiments, including patients who are Jehovah’s Witnesses, provide key insights. Because these patients typically decline transfusion of blood products, they offer a rare glimpse of what happens when patients crash below the thresholds and are treated without the use of blood.

A 1994 cohort study reported on the experience of 61 Jehovah’s Witnesses patients with hemoglobin concentrations ≤8 g/dL. Of the 23 patients who died as a result of anemia, all but three (each of whom had undergone cardiac surgery) had a hemoglobin value <5 g/dL.

The lowest hemoglobin reported for a survivor was 1.4 g/dL. The patient had been diagnosed with placenta previa and experienced massive hemorrhage. She was treated with 100% FiO2, intravenous fluids and iron, and total parenteral nutrition. In order to decrease oxygen consumption, she was intubated and paralyzed and cooling was employed. A right heart catheter noted a cardiac output of 10 liters/min, which the authors hypothesize was made possible by the decrease in blood viscosity resulting from the markedly low hemoglobin.

Although nobody will argue that the transfusion threshold for asymptomatic patients should be lowered to 1.4 g/dL, the physiologic response to anemia suggests that many might do well below 7 g/dL. In the future I’ll review physiologic reasons for why this might be. At the very least, it seems reasonable to wonder whether patients might be better served being offered blood transfusions to treat symptoms rather than a number.

For now, I will offer a few closing thoughts. First, I see the Origin Story of numeric transfusion thresholds as a demonstration of the power of slow and layered advancements in knowledge and skill. The first threshold - 10 g/dL - only emerged because scientific breakthroughs afforded anesthesia a new opportunity to raise a number with the hopes that this would help their patients. Once the idea of a threshold became acceptable, other fields within medicine grabbed hold and expanded its use to all patients, not just those with signs or symptoms that would have historically warranted intervention. And 10 g/dL persisted, in part because the number just seems better than 9 or even 11. So things remained until the introduction of randomized trials showing that values as low as 7 g/dL were safe. However, these trials did nothing to dispel the notion that all patients should be above 7 g/dL. And so here we are in 2023, offering blood not to remedy a symptom or treat a condition. Instead, we offer blood to treat a number.

And this practice has societal support.5 The most recent Association for the Advancement of Blood & Biotherapies (AABB) guidelines, published in October 2023, favor a threshold of 7 g/dL: “For hospitalized adult patients who are hemodynamically stable, the international panel recommends a restrictive RBC transfusion strategy in which the transfusion is considered when the hemoglobin concentration is less than 7 g/dL (strong recommendation, moderate certainty evidence).” Though they consider it “good clinical practice to consider not only the hemoglobin concentration but also symptoms, signs, other laboratory data, patients’ values and preferences, and the overall clinical context” the recommendation does not include any of the qualifiers. The threshold itself is enough.

In a twist of irony, it is the American Society of Anesthesiologists that offers the only6 value below 7 g/dL, writing, “A restrictive red blood cell transfusion strategy may be safely used to reduce transfusion administration. The determination of whether hemoglobin concentrations between 6 and 10 g/dl justify or require red blood cell transfusion should be based on potential or actual ongoing bleeding (rate and magnitude), intravascular volume status, signs of organ ischemia, and adequacy of cardiopulmonary reserve.”

Returning to the AABB guidelines, they close with the following appeal: “Given the findings indicating the safety of restrictive thresholds, new trial designs should focus on the safety of lower transfusion thresholds (e.g., 5-6 g/dL), incorporation of physiologic parameters, and the conduct of health economic analyses.”

I could not agree more.

Or hematocrit, if you asked me between 2009 and 2013.

One interesting observation is that we do not aim to restore patients to their normal hemoglobin. This is unlike electrolyte thresholds (e.g., potassium) where we aim for “the black.” I have assumed that this relates, at least in part, to the idea that homeostasis is best maintained with such an approach.

A case-control study of 125 surgical patients who declined blood transfusions for religious reasons reported increasing operative mortality as hemoglobin fell from >10 g/dL (7%) to <6 g/dL (62%). This study was not published until 1988, well after 10 g/dL had become a fixture in preoperative care.

I am using 7 g/dL here, recognizing that some conditions favor a higher threshold.

Curiously, UpToDate makes no mention of what we should do with the asymptomatic patient with anemia.

Others may exist, but this is all that I could find.