How "≥250 PMNs = SBP" came to be

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis is an example of how a number defines a condition. It is also an example of how our first definition is often our last one too.

As I noted in a recent post, numeric thresholds fascinate me. In particular, I’m intrigued by the concept that a condition may be defined by a single value. For some conditions (e.g., hyponatremia) this makes sense. Hyponatremia is a low serum sodium so this finding is necessary and sufficient. In other situations, a value helps define an essential component of a condition. To diagnose acute myocardial infarction we need evidence of myocardial injury; this is typically identified with an elevation in troponin.

But what about conditions where the diagnosis is made by a surrogate marker alone? Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) is an example. The most recent American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) guideline writes that “The diagnosis of SBP/SBE1 is established with a fluid polymorphonuclear (PMN) leukocyte count >250/mm3.” No symptoms are necessary. Or culture data. Just an ascites PMN count >250/μl.2

The story of how 250 became our threshold is instructive, not just because it provides insights into an important condition, but also because it sheds light on how arbitrary the process can be. And how once we’ve settled on something, change is difficult.

SBP emerges, almost out of thin air

According to John Dever, SBP was first described in 1907 by Krencker.3 Others made similar observations in 19584 and 1963. Then, in 1964, Harold Conn used the term ‘spontaneous bacterial peritonitis’ for the first time. There is little doubt that SBP existed before 1907 and certainly before 1964. But, the rarity of paracentesis made us blind to the diagnosis. As paracentesis became more common, so did SBP.

Almost immediately after the condition was identified, difficulties in diagnosis became clear. The initial case series required positive ascites or blood culture for inclusion. This is not a workable screening test for clinicians. For one, culture results are not immediately available. When paired with the fact that untreated SBP is highly morbid, an alternative method for early diagnosis became essential. Unfortunately, the obvious surrogate - a positive gram stain - is unreliable. Fewer than a third of ascitic fluid stains from patients with SBP are positive. A more sensitive alternative was needed.

WBC comes first, then PMNs

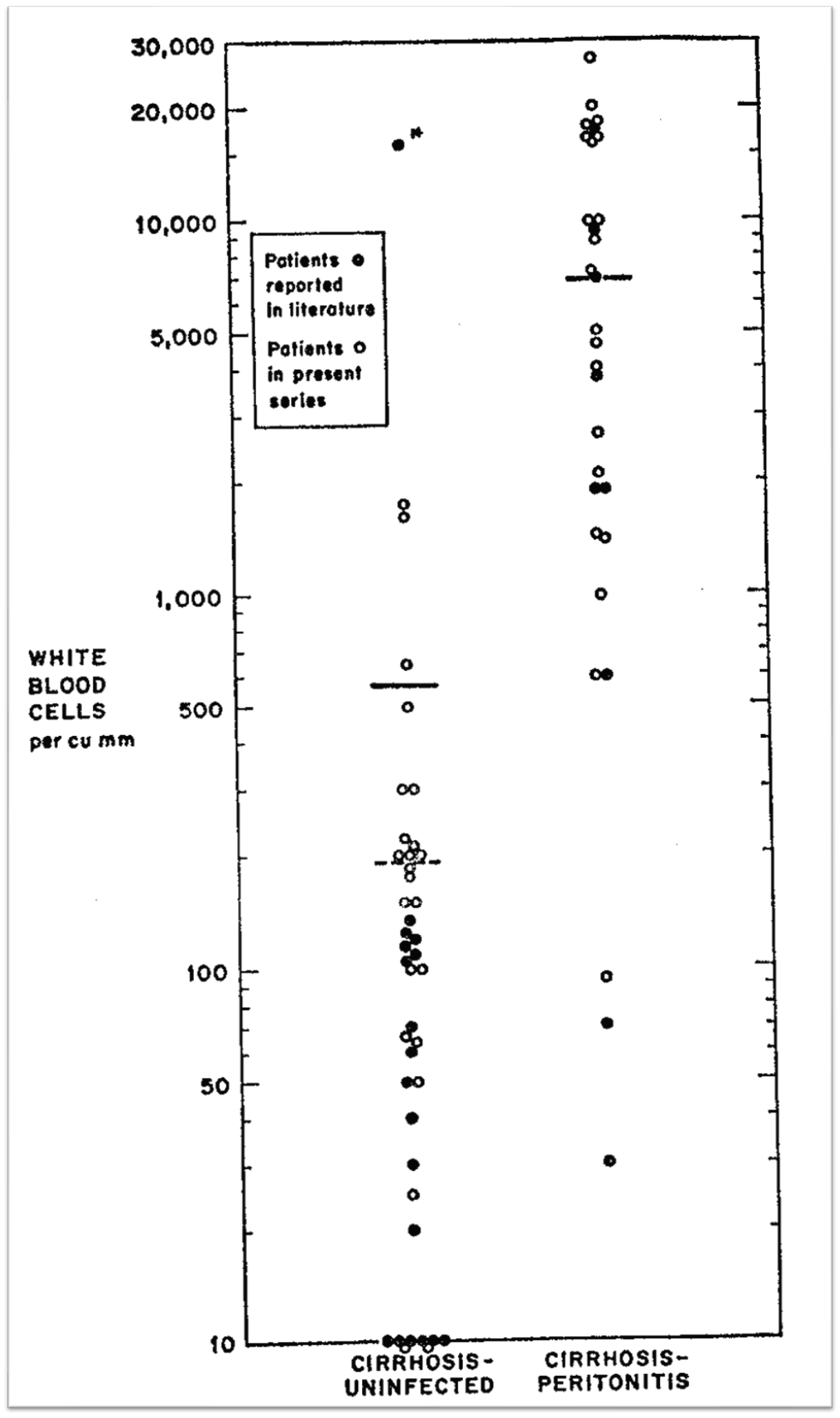

In one of the first large SBP case series, Conn and Michael Fessel observed that “the number and type of leukocytes in ascitic fluid appear to provide valid diagnostic information.” Below is a figure from their study showing total white blood cells (WBC) in patients with and without SBP. I’ve removed the WBC labels (y-axis) and marked four different values that might be considered as thresholds. Have a look and indicate which you suggest as best.

Here is the figure with the values showing:

Based on these results, the authors propose that a total WBC >300/μl (line 4 above) provides a reasonable threshold for treatment. See if you agreed. Even if you didn’t, this threshold was supported in studies published in 1974 and two published in 1976. We were getting somewhere.

Then, in 1977, Stephen Jones became the first to suggest that the polymorphonuclear cell count be used. Using a positive ascites culture as the standard, he found that 10/11 (91%) of patients with SBP had a PMN count >250 cells/μl and 5/57 (9%) of patients without SBP had a PMN count >250 cells/μl. Here is the relevant Figure:

Subsequent studies published in the late ‘70s supported either >1000 WBC/μl (85% of which needed to be PMN) or WBC >500 cells/μl. Clearly, no consensus test (WBC or PMN) or threshold value had been found.

Then something interesting happened. Three papers were published, one each in 1982, 1983, and 1984. These three studies used a PMN threshold of 250 cells/μl - along with a positive ascitic fluid culture and the absence of a primary source of infection - as diagnostic criteria for SBP. They do so without offering a citation or explanation for their choice. As later authors would observe, this threshold was arbitrarily set. It isn’t as though no data existed supporting 250 PMN/μl. Again, Jones had suggested this value. But the literature to that point had not converged around this value. It was still in its infancy. And yet, with these studies, >250 PMN/μl was crowned as the threshold for SBP.

Fast forward to 1991. That year, Bruce Runyon and Mainor Antillon published a study evaluating the utility of ascitic fluid pH and lactate in the diagnosis of SBP. Consistent with the three studies published in the early 1980s, the authors stated that “SBP was diagnosed when the culture grew pathogenic bacteria, the neutrophil count was equal to or more than 250 cells/mm3 and no intraabdominal surgical source of infection was present” without offering a supporting citation. Later, they provide the following test characteristics for the diagnosis of SBP:

Maybe I’m misguided, but I find it deceiving to include ≥250 PMN/μl in this Table. Their definition of SBP required ≥250 PMN/μl so of course that threshold will be 100% sensitive. The casual reader who scans this study could not be faulted in interpreting Table 4 as supporting ≥250 PMN/μl as the best test for SBP. Or at least it’s most sensitive.

By 1992, we finally had enough data for Guadalupe Garcia-Tsao to perform a comprehensive review. Here is a summary of the data from eight prospective studies:

Garcia-Tsao concluded that a “PMN count of >500/mm3 is still the best predictor of SBP, with a sensitivity of 80%, a specificity of 97%, and a diagnostic accuracy of 92%.” But it was too late for 500. It would not supersede 250.

The 1992 summary was updated, in 2008, by a systematic review in JAMA’s Rational Clinical Exam series. Camilla Wong, Jayna Holroyd-Leduc, Kevin Thorpe, and Sharon Straus include 16 studies in their analysis. Have a look at the numbers below and indicate in the poll which test you would recommend be used to diagnose SBP:

Here’s Table 4 from the review.

I think it is safe to say that an ascitic fluid PMN >500 cells/μl is the best test in the above Table. It has the highest positive LR and the lowest negative LR. It is hard to beat that combination.

In what I’d call an odd turn, the authors write that “While the literature supports a threshold of greater than 500 cells/µL as most accurate, most experts initiate antibiotic therapy when the PMN count is greater than 250 cells/µL, given still the greatly increased likelihood of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis at this lower PMN count threshold (summary LR, 6.4; 95% CI, 4.6-8.8) along with the potential fatality of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.”

The most recent AASLD guidelines use this JAMA systematic review to support their use of 250 PMNs/µL, writing that “the diagnosis of SBP or SBE is established with a fluid (ascites or pleural, respectively) absolute neutrophil count greater than 250/mm3, a cutoff with the highest sensitivity chosen to avoid SBP being untreated.”

I recognize that the mortality of SBP demands that we choose a sensitive test. I don’t accept that the data best supports 250 cells/µL as the threshold. If the avoidance of false negatives was a primary goal, why not lower the value even further? Shouldn’t we demand a sensitivity of nearly 100%? And if we are aiming for a balance between sensitivity and specificity, >500 PMNs/µL should have been resurrected.

Variants emerge

The evolution towards our PMN threshold of 250/µL becomes more complicated when you consider two SBP variants described in 1984 (culture-negative neutrocytic ascites) and 1990 (monomicrobial non-neutrocytic bacterascites).

In 1984, Runyon and John Hoefs compared patients with positive ascites cultures to those with negative ascites cultures. Realizing that the presentation and outcomes of these patients are similar, they suggested that culture-negative neutrocytic ascites (CNNA) be considered a variant of SBP and treated similarly.

Notice that the appearance of CNNA meant that the previous gold standard - positive ascitic culture - was no longer deemed sensitive enough. Instead, the newly anointed PMN count >250/µL became the gold standard. Even though it had been validated using the test - positive ascitic culture - that it was now replacing!

Things became even weirder when Runyon first described monomicrobial non-neutrocytic bacterascites (MNB). In this SBP variant, the ascitic culture is positive but the PMN count is <250/µL. Runyon observed 62% of bacterascites episodes spontaneously became sterile without treatment and concluded that MNB is a “common variant of ascitic fluid infection that may resolve without treatment or may progress to spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.”

Now, not only had the previous gold standard been superseded by the PMN count, but it had been relegated to the realm of “false positive” in some cases! And recall that the PMN count emerged as our “most sensitive test” when it was evaluated using a positive ascitic culture as the gold standard. It’s so circular as to make your head spin.

Concluding Remarks

Let me state clearly that I believe a PMN threshold of 250/µL works. It has been shown, over decades, to be a valuable diagnostic tool for SBP. Given this, I tend to agree with Wong et al that we needn’t move the need up 500 PMNs/µL or down to ensure an even greater sensitivity. If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.

With that said, it is important to acknowledge that 250 PMNs/µL solidified its place while the data was nascent and may not have been chosen were we to reset the clock. In some ways, this is similar to another set of threshold tests that emerged around the same time: Light’s criteria. First described in 1972, these criteria have fought back many challengers in the intervening years and contain the thresholds most of us use today.

A PMN threshold of 250/µL isn’t going anywhere. This value is synonymous with SBP. The anniversary of their marriage is going on 50 years and is likely to remain strong for another 50. But, as with any longstanding relationship, it is far more complex than it first appears.

SBE = Spontaneous bacterial empyema

This is a very minor point, but one worth mentioning. AASLD uses “>250” while nearly every other source uses “≥250.” I know it is exceedingly unlikely to see a patient with exactly 250 PMNs/mm3, but it isn’t possible. AASLD says they don’t have SBP. Others say they do.

This article is in German. I didn’t try to translate it and confirm Dr. Dever’s finding.

This one is in French. Also not translated. Sorry.