I’ve seen many changes in practice over my career. Some are changes in language (e.g., we’ve moved from “acute renal failure” to “acute kidney injury”). Some are changes in diagnostic testing (e.g., I now rarely order a carotid ultrasound to evaluate syncope). Some are changes in therapeutics (e.g., levofloxacin is no longer my initial choice for pneumonia).

But medicine is resistant to change. In this way, it is a conservative profession. There are thousands of new studies published each year and yet what I do, day-to-day, is largely unchanged year-over-year. If you examined the orders written for patients under my care, the 2023 set would appear quite similar to the 2013 set. Ceftriaxone, aspirin, ECGs, physical therapy, and so on. Most of what I do stays the same. So when something changes quickly, easily, and uniformly among my peer groups it provides an interesting opportunity to examine why. Iron repletion, particularly oral iron repletion, provides an interesting case study.

Over the last 5 years, I have seen a near-complete change in the way iron deficits are replenished. First, the use of IV iron extends far beyond what I saw early in my career. It is now the first choice for many patients found to have iron deficiency while hospitalized. But the sea change in how oral iron is administered is far more interesting.

When I was an internal medicine resident, I learned that iron needed to be dosed daily or even two or three times a day. But now, every other day iron is the clear standard. This shift has occurred over the last six years, since the publication of a 2017 study. If a landmark trial is defined as one that results in a change in practice, this study of 60 patients fits the bill.

Published in Lancet Haematology, the report includes two prospective, open-label, randomized controlled trials. In the first trial, women were randomized to receive either 60 mg of iron on consecutive days for 14 days or the same doses on alternate days for 28 days. It is this trial that has led to practice change. Looking at the women included, approximately half were iron deficient (defined as a serum ferritin <15 µg/L) with a mean value of 13.8 µg/L in both arms. These patients were also, on average, mildly anemic (hemoglobin 12.8 and 13.2 g/dL in the two arms).

At the end of the study, the cumulative fractional iron absorption was 16.3% in the consecutive-day group versus 21.8% in the alternate-day group (p=0·0013). The cumulative total iron absorption was 131 mg versus 175 mg (p=0·0010). Here is a Figure from the study demonstrating the higher fractional iron absorption in the every other day group.

What explains these findings? The investigators found that during the first 14 days of supplementation, serum hepcidin was higher in the consecutive-day group than in the alternate-day group (p=0.0031). Because hepcidin limits iron absorption, increased values should lead to exactly what these authors report.

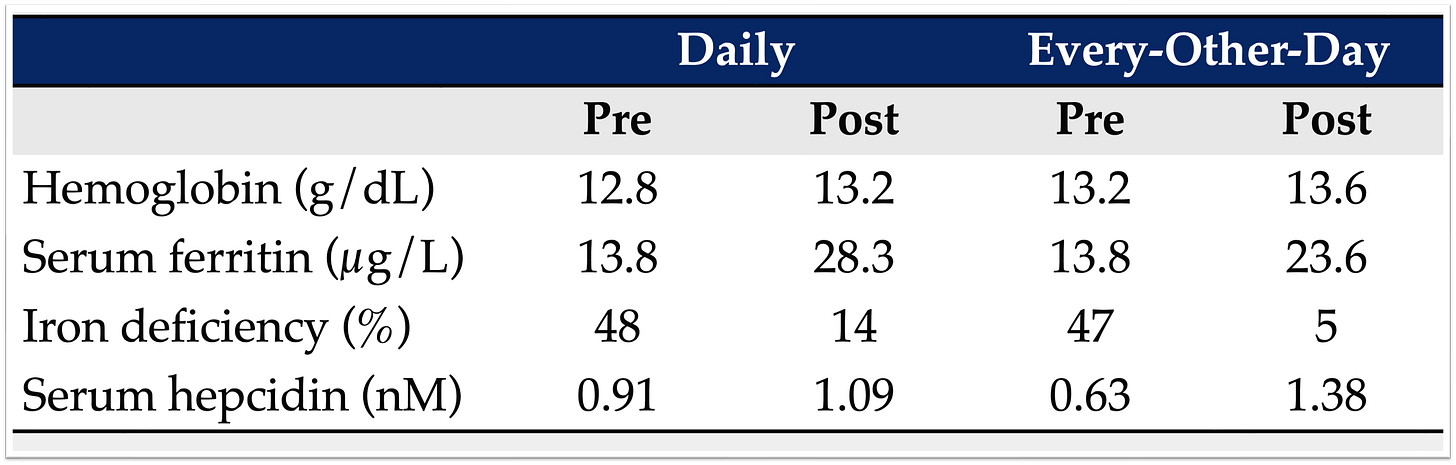

But when you examine Table 3 (I have extracted the key data below), which reports measurements after the final iron supplement intake, serum hepcidin levels were higher in alternate-day dosing (1.38 nM) when compared to consecutive-day dosing (1.09 nM). And here’s how the participants’ hemoglobin and serum ferritin changed:

Notice that this study found no difference in hemoglobin and no difference in serum ferritin. And yet, based on these results, the authors conclude that “providing iron supplements on alternate days and in single doses optimises iron absorption and might be a preferable dosing regimen.”

I recall hearing about this study very soon after its publication. And almost immediately I began to see practice change. On rounds, residents would enlighten interns about this new data, and orders for daily oral iron would promptly be changed to every other day. What explains the dramatic adoption of every other day oral iron? Put another way, why did the standard of care alter based on a small study that demonstrated no meaningful change in iron status?

I don’t think it can be attributed to this study being published in a widely read journal. Though Lancet Haematology has an impact factor north of 20, it isn’t something most internal medicine trainings are perusing routinely. The study was mentioned in NEJM Journal Watch in October 2017, but I also doubt this can explain the groundswell in practice change. And though I am a firm believer in the power of social media, Twitter/X in particular, I don’t see this as the main platform leading to this change either.

Instead, I wonder if this could represent what I’ll call The Curbsiders Effect. The highly influencial podcast1 covered this study in a February 2018 episode, just months after it was published. The guest was Michael Auerbach, an expert on iron and the author of an editorial published alongside the 2017 study.

Citing the study, The Curbsiders, offer this clinical pearl: “Oral iron is effective, but poorly tolerated. Gastrointestinal side effects are reported by ~70% of patients. It should be dosed once every other day.” Given that the show has more than 40,000 downloads per weekly episode it has the ability to reach far more people than can an individual publication in a subspecialy journal. There are ~550 internal medicine programs in the country. It is not hard to imagine that 1-2 residents at each program are among the tens of thousands of Curbsiders listeners. Surely more listen than do read Lancet Haematology. If so, one might imagine these few residents sharing their new knowledge and engendering change.

But these numbers also show that there must be more to it. Though The Curbsiders have a large audience, it isn’t enough for them to endorse a practice. They simply do not have enough penetrance among oral iron prescribers. The listener must share their new fact and convince others. Culture must change. In the case of oral iron replenishment, I think there are a number of additional factors at play:

As demonstrated by The Curbsiders pearl, it is easy to encapsulate this practice change in a soundbite. Something that requires minutes of explanation is less likely to be immediately implemented. But “every other day iron is better absorbed…” can be mentioned on rounds, almost in passing, and without the need for deep discussion.

This practice change is easy to implement. No approval from infectious disease is necessary. You needn’t “run this by the attending” or “check with pharmacy.” The order takes seconds to write or edit.

This practice change isn’t taking anything away or adding anything new. It’s just a dose change. For those resistant to change, this provides tremendous comfort.

If we’re wrong, there is little downside (more on this in future posts).

It feels good to practice evidence-based medicine and feel like you’re “in the know.”

Fast-forward to November 2023. The same group has now published a follow-up randomized placebo-controlled trial with patient-centered outcomes. In it, 150 women with a serum ferritin ≤30 μg/L were assigned to either 100 mg oral iron daily for 90 days, followed by a daily placebo for another 90 days or the same daily dose of iron and placebo on alternate days for 180 days (alternate-day group). Here’s what they found after three months:

Unsurprisingly, at 93 days the patients taking daily iron had a higher serum ferritin (light blue shade) and higher hemoglobin (light green shade). The p-value for both comparisons was <0.05. Also unsurprising, the serum hepcidin was higher in the daily iron group (light gold shade); p<0.001. At this point, the daily group had gotten all the iron they were going to get and the every other day group had only gotten 50% of what they were going to get.

At 186 days, the hemoglobin values were no different but the serum ferritin levels had plummeted in the daily group and continued to improve in the every other day group. You can see that in this Table:

This is no surprise. Those assigned to daily oral iron hadn’t been taking any supplement for 3 months! Of course their ferritin will once again decline during that period. Consistent with this is the fact that the serum hepcidin decreased in the daily iron group during the second 90-day period.

For the primary outcome, the authors appropriately compared serum ferritin at 90 days in the daily group to 180 days in the every other day group. This is the period when each set of participants received the same total iron dose. Here, the ferritin values were essentially identical (43.8 μg/L versus 44.8 μg/L). This cross-over at 90 days is demonstrated well in Figure 2:

It is important to note that side effect was more common with daily dosing. At 90 days, 9.5% of those receiving daily iron had side effects; at 180 days, 5.0% in the every other dose group (p<0.0001). Most of the symptoms were reported as mild. For many, myself included, part of the allure of every other day iron is the belief that I might get a two-fer. Not only would iron absorption be increased, but I might also be causing fewer gastrointestinal side effects. Who wouldn’t go for this? But, the 2023 study suggests that, at best, this is a one-win proposition.

And it isn’t the first study to throw shade at the initial findings form 2017. At least four other randomized trials have been published over the last few years:

Internal Medicine Journal, January 2020. 150 participants with iron deficiency anemia. Three arms were included (twice daily, daily, and every other day). At one month, there was no difference in hemoglobin or ferritin between the daily and every other day groups. The twice daily group had a higher ferritin. Nausea was more common in the twice daily group.

Annals of Hematology, January 2020. 62 participants with iron deficiency anemia. Two arms were included (twice daily and every other day). At six weeks, the hemoglobin value was higher in the twice daily group. Hepcidin levels were no different. Rates of gastrointestinal side effects were no different.

Journal of The Association of Physicians of India, May 2020. 40 participants with iron deficiency anemia. Two arms were included (daily and every other day). At twenty-one days, the every day group had a higher hemoglobin value. Nausea was more common in the daily group.

Scientific Reports, February 2023. 200 participants with hemoglobin <10 g/dl and a ferritin <50 ng/mL. Two arms were included (daily and every other day). At eight weeks, there was no difference in change in hemoglobin or ferritin. Nausea was more common in the every other day group.

Taken together, the data show no consistent benefit from every other day iron supplementation, when compared with daily dosing. And even those who reference an improved side effect profile should recognize that this finding is also inconsistent with at least one trial showing more nausea with every other day dosing.

In the end, I don’t think it much matters if you or I prescribe daily or every other day dosing. Whomever is taking these supplements should be monitored for improvements in ferritin, hemoglobin, and symptoms of both anemia and iron deficiency and side effects of the treatment. Dosing regimens can be changed to reflect how the patient is responding.

Still, I remain fascinated by how quickly and easily I and others around me adopted every other day iron. Whether this demonstrates The Curbsiders Effect, attention to evidence based medicine, or some other factor, isn’t entirely clear. Medicine often demands that we “wait for confirmation” from larger, bigger, and better studies. Here, that wasn’t the case. It seems as though just the right study examining just the right question was able to topple decades of practice. And I highly doubt we’re going back, even though what’s followed isn’t as convincing. Culture change is rare. Seeing it twice for the same condition/treatment would be miraculous.

Disclosure: I have been a guest on The Curbsiders and am a big fan.

I think it’s entirely plausible that a podcast with a good sized following could lead to detectable, broader changes in practice--especially if it gives attention to studies that otherwise wouldn’t get it, and if listeners are in position to spread practice patterns. Media attention has been shown to sway practice patterns, presumably through influence on patients and doctors alike; Curbsiders obviously would impact doctors more. I’d be curious to see if there were practice pattern changes in the data when the podcast covered an *older* study, so that we could attribute changes to the podcast rather than other news coverage of a new study. We did something similar here looking at oral minoxidil for hair loss after some old studies got new attention in the New York Times: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/article-abstract/2804659

I think also contributing to the rapid spread was the contrarian spirit of certain people in internal medicine (e.g., "Well, actually...ALLHAT used Chlorthalidone"). As in, "Well, actually...iron is better absorbed QOD." Thus QOD dosing became a shibboleth of that type of contrarian practice -- until *now*, when what you show is that daily dosing is the contra-contrarian practice. I cannot wait to counter the residents with *these* data while precepting. :)